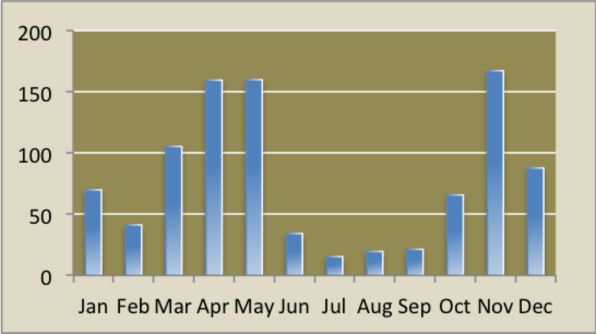

The forest, as Nairobi, has two wet seasons: April to June and October to December. In July and August it is cool, cloudy and dry. From August to December it is sunny and dry. January, February and early March are hot and dry months.

The average annual rainfall is 930 mm (37 inches), varying from 1250 mm (50 inches) during wet El Niño periods to 350 mm (14 inches) during drought spells. The peak average rain months are April, May and November (see chart, below).

Temperatures throughout the year vary according season, cloud and sunshine, but the range is from 8° C (45° F) on a chilly August morning to 28° C (82° F) on sunny February afternoon.

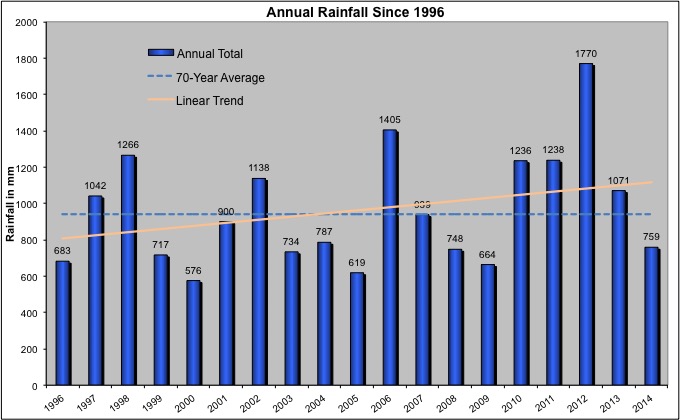

2012 appears to have been the wettest year in 67 years: nearly twice the long-term average (dotted line in the chart above). Rainfall measurements taken near Karura’s southern boundary since 1945 at the Muthaiga Country Club suggest that only the famous flood year 1963 came close to the 1,770 mm (70″) measured along the Gitathuru River.

The April 2012 total of 512 mm was the most ever recorded for that month, and December’s 300 mm was second only to Dec ’63. Moreover, records in recent years show an increasing annual trend (orange line in chart). Anyone still doubt the climate is changing?

The forest sits on million-year-old Late Tertiary volcanic rocks. Technically speaking, the common rock forms are volcanic tuffs with intercalated flows of basaltic sponge cake. Both types are occasionally exposed in Karura’s deeper river valleys, and the tuffs yield the familiar grey building stone of Nairobi. “Chimneys” of larva are occasionally found exposed on ridges in the western and middle sections of the Forest.

The Karura landscape rolls gently between and through shallow valleys. Drainage is generally southeasterly. Depressions throughout the forest impede drainage and cause formation of small edaphic grassy swards and swamps, some of which are under threat from thirsty Eucalyptus trees.

Five perennial tributaries of the Nairobi River pass through the forest running roughly west to east and cutting through gently undulating landscape. These are:

The Karura River valley offers a precarious and stunning descent through indigenous forest to the large waterfall and the Mau-Mau caves.

Since the Late Tertiary period, during the formation of Mt. Kenya and Kilimanjaro, the region has experienced only moderate tectonic disturbances. Consequently, the parent rocks have undergone deep weathering, resulting in uniform soil profiles. In natural forest environments, this weathering produces very deep, reddish-brown clayey loam soils with slow but adequate drainage. These soils tend to become highly adhesive when wet and dry rapidly, often developing shrinkage cracks. The upper layers of soil typically exhibit a dark brown hue due to the incorporation of humus, without a significant buildup of deep litter.

In areas covered by grassland with good drainage, the soil composition closely resembles that found beneath forest stands. However, in low-lying regions subject to intermittent waterlogging, a distinct soil type emerges. These areas experience fluctuating water tables, with some fine soil material being transported downhill from adjacent higher elevations. The resultant soil in these low-lying areas is typically heavy, dark grey clay, often stained black by undecomposed humus, commonly referred to as ‘black cotton’ soil. Below the clay layer, ranging from 5 centimeters (2 inches) to one meter (approximately 3 feet) deep, a red-brown laterite layer forms. This laterite is a product of re-cementation rich in iron compounds, often associated with swampy conditions and varying water tables.

Overall, forest soils in the region are highly conducive to tree growth, except in areas with impeded drainage, such as swampy sites. These locations often give rise to natural grassy clearings, characteristic of Kenya’s upland forests.

Forest plantations cover approximately 630 hectares, featuring species imported from South America, Australia, and the Asian sub-continent. Among these are Araucaria cunninghamii, Grevillea robusta, Eucalyptus saligna, E. globule, Cupressus torulosa, and Cupressus lusitanica.

Most of the plantations in the forest have surpassed their economic rotation age. Eucalyptus trees range from 38 to 83 years old, Araucaria from 44 to 46 years, and Cupressus from 34 to 46 years. Many of these plantations are already showing signs of age-related drying. As part of the FKF-KWS management plan, efforts are underway to replace the degraded plantations with indigenous species.

Indigenous trees cover approximately 260 hectares, excluding about 25 hectares in the largely alienated 110-hectare area east of Kiambu Road. Species within this category include Olea europeae subsp. auspidata, Croton egalocarpus, Warburgia ugandensis (known locally as Muthiga), Brachyleana huillensis (referred to as Muhugu, the iconic image on the FKF logo), Uvaridendron anisatum, Markhamia lutea, Vepris nobilis, Juniperus procera (Cedar), Craebea brownii (with a notable specimen located just outside the largest Mau-Mau cave), Newtonia buchananii, Salvadora persica (known as Mswaki or the Toothbrush Bush), Ficus thonningii (Mugumu), Trichilia emetica, Calondendrum capense, and Dombeya goetzenii.

Additionally, several shrubs with wide local medicinal use are also present. These include Strychnos henningsii (Muteta), Erythrococca bongensis (Muharangware), Vangueria madagascariensis (Mubiro), Rhamnus prinoides (Mukarakinga), Caesalpinia volkensii (Mubuthi), Solanum incanum (Mutongu or Sodom Apple), Elaeodendron buchananii (Mutanga), and Rhus natalensis (Muthigio).

The name ‘Muthaiga’ (the neighbourhood forming the southern boundary of the main Karura forest) derives from the Kikuyu name — ‘Muthiga’ — of the East African Greenheart tree, Warburgia ugandensis? Look out for the dark green elongated leaves and the knobbly, reddish-brown bark. You can often see where a chunk of bark has been harvested by a traditional herbalist to infuse as a remedy for chest pains, colds, malaria and toothache, or in a stew: most parts of the tree have a hot, peppery taste.

The riparian belts along the Gitathuru and Ruaka streams host groves of Arudinaria alpina, Kenya’s native bamboo species. The exotic giant bamboo Dendrocalamus giganteus is mainly found growing within the tree nursery along the Karura River. Additionally, small wetlands are found throughout the forest (occupying some 10 ha). These provide important habitats for birds and bird watchers.

Indigenous orchids — representatives of nine Kenyan species — have been re-introduced to Karura Forest thanks to generous donations of plants from members of the Kenya Orchid Society in August 2012. With the assistance of Friends of Karura Forest, Alexandra Contos and Daniel Odhiambo (striped shirt), one of Kenya’s foremost orchid experts, carefully placed the plants in suitable mid-canopy positions. Below is one of the Aerangis already in flower.

The forest is known to host a variety of animals. These include the Suni, Harvey’s Duiker, Bushbucks, Bush Pigs, Genets, Civets, Honey Badgers, Bush Babies, Porcupines, Syke’s Monkeys, Bush Squirrels, Hares and the Epauletted-Bat. A Side-striped Jackal has been recorded in Sigiria.

A rare glimpse of a family of three African clawless otters captured on one of the FKF ‘KaruraKam’ camera traps.

A young female bushbuck who took up residence in the reforestation area not far from the Limuru Road gate. She seemed quite relaxed among the protected young trees. The only problem she had was all the flies that emerged with the good October 2012 rains.

To date, some 200 bird species have been seen in the forest. These include Ayres Hawk-eagle, the African Crowned Eagle, the Silvery-cheeked Hornbill, Hartlaub’s Turaco, the Narina Trogon, the African Wood Owl, Crested Cranes, Sparrows, Doves, Weavers and Vultures. The call of the African Snipe has been heard at Lily Lake.

As you walk around Karura, listen for the guttural ‘wau-wau-wau..’ of Hartlaub’s Turaco. You’ll probably just see a flash of his red wing-feathers, or, with luck, find one (photos H. Croze).

A pictorial list of the main bird species (compiled by Mr. Amedeo Buonajuti) is available at the entrances to the forest free of charge.

A magnificent Crowned Eagle carries off an unfortunate Suni dwarf antelope

Reptiles include the rock pythons, numerous other harmless snakes, plated and monitor lizards.

A detailed inventory of non-vertebrate species is planned. Preliminary collections have been undertaken by ICIPE, the International Center for Insect Physiology and Ecology, and you may catch a glimpse of white, tent-like insect traps within the forest.

The forest provides habitat for numerous species of butterflies, including the African Queen and the Desmond’s Green Banded Swallowtail (see the images on the back of the Karura Forest Map).

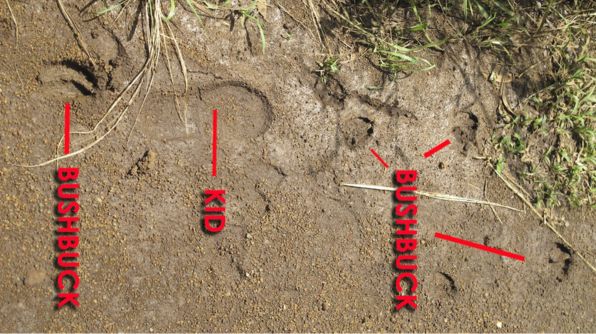

The rains give opportunities for spotting animal tracks. Here are some bushbuck tracks along the road between Junction 6 and the entrance to KFEET. It’s probably an adult male, judging from the size of the track compared to that of a kid or small woman who walked along the road as well. The bushbuck probably comes out at night to browse along the roadside bushes.

Photo tip: to get the most out of a track shot, make sure the track is between you and the sun.

The Friends of Karura is a Community Forest Association comprising Kenyans and other champions of participatory forest management who are dedicated to protecting for future generations the city’s largest green area, the Karura Forest Reserve.

Legal terms and information: Privacy Policy . Terms and Conditions