The riparian belts along the Gitathuru and Ruaka streams host groves of Arudinaria alpina, Kenya’s native bamboo species. The exotic giant bamboo Dendrocalamus giganteus is mainly found growing within the tree nursery along the Karura River. Additionally, small wetlands are found throughout the forest (occupying some 10 ha). These provide important habitats for birds and bird watchers.

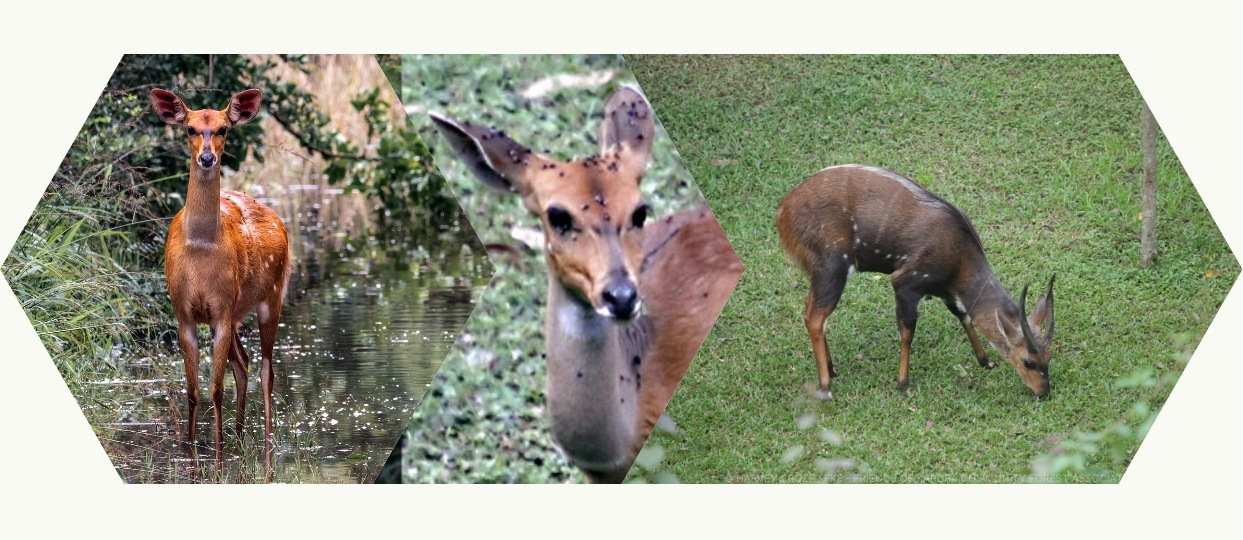

The forest is known to host a variety of animals. These include the Suni, Harvey’s Duiker, Bushbucks, Bush Pigs, Genets, Civets, Honey Badgers, Bush Babies, Porcupines, Syke’s Monkeys, Bush Squirrels, Hares and the Epauletted-Bat. A Side-striped Jackal has been recorded in Sigiria.

A rare glimpse of a family of three African clawless otters captured on one of the FKF ‘KaruraKam’ camera traps.

To date, some 200 bird species have been seen in the forest. These include Ayres Hawk-eagle, the African Crowned Eagle, the Silvery-cheeked Hornbill, Hartlaub’s Turaco, the Narina Trogon, the African Wood Owl, Crested Cranes, Sparrows, Doves, Weavers, and Vultures. The call of the African Snipe has been heard at Lily Lake.

A pictorial list of the main bird species (compiled by Mr. Amedeo Buonajuti) is available at the entrances to the forest free of charge.

Reptiles include the rock pythons, numerous other harmless snakes, plated and monitor lizards.

A detailed inventory of non-vertebrate species is planned. Preliminary collections have been undertaken by ICIPE, the International Center for Insect Physiology and Ecology, and you may catch a glimpse of white, tent-like insect traps within the forest.

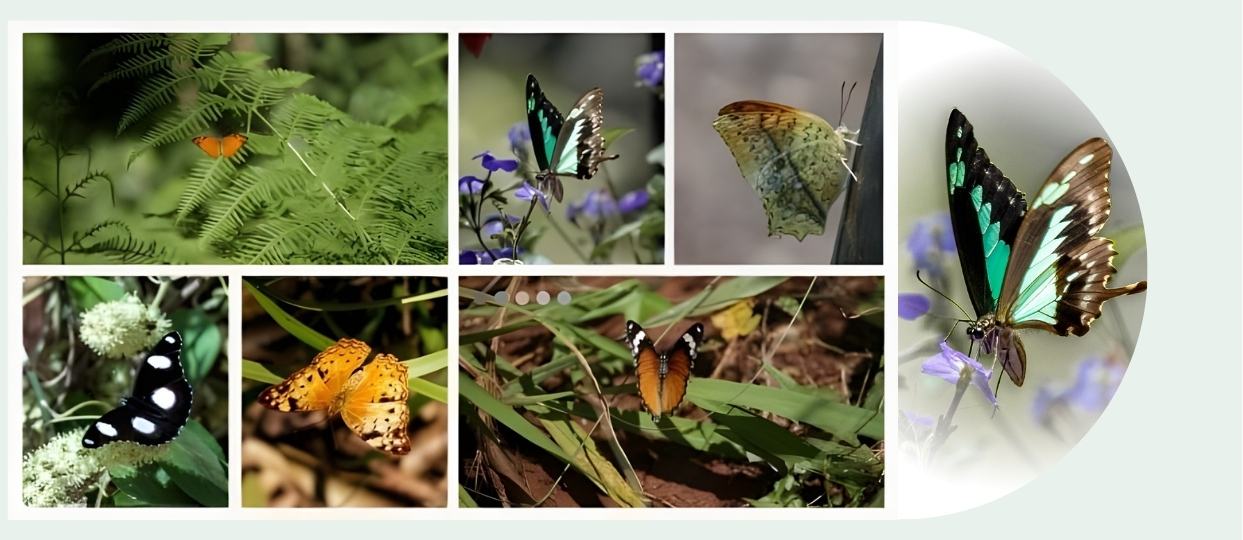

The forest provides habitat for numerous species of butterflies, including the African Queen and the Desmond’s Green Banded Swallowtail (see the images on the back of the Karura Forest Map).

The rains give opportunities for spotting animal tracks. Here are some bushbuck tracks along the road between Junction 6 and the entrance to KFEET. It’s probably an adult male, judging from the size of the track compared to that of a kid or small woman who walked along the road as well. The bushbuck probably comes out at night to browse along the roadside bushes.

Photo tip: to get the most out of a track shot, make sure the track is between you and the sun.

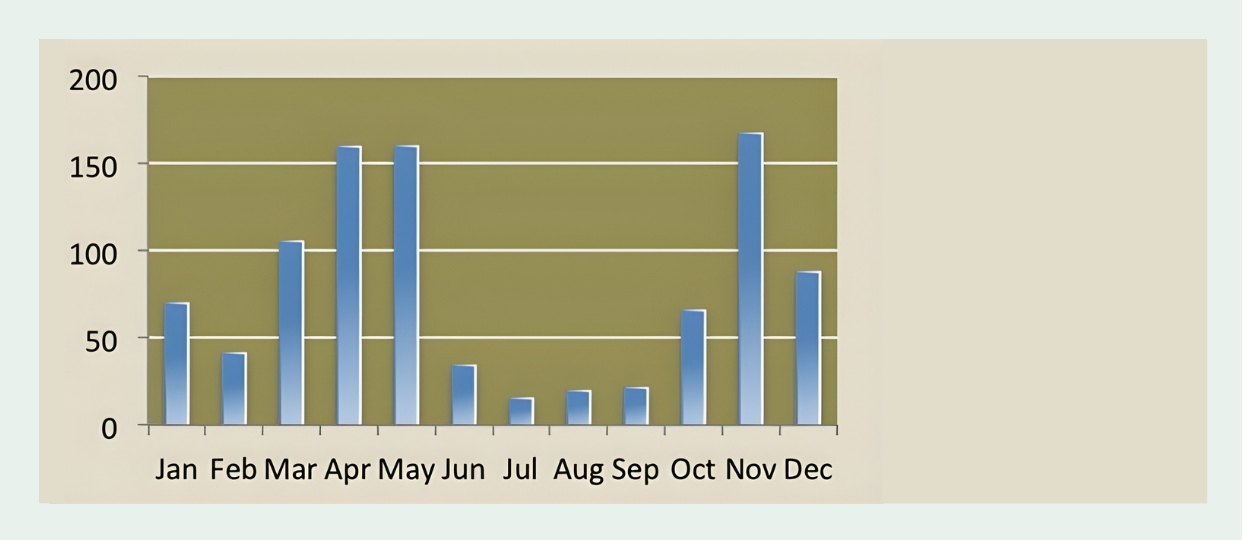

The forest, as Nairobi, has two wet seasons: April to June and October to December. July and August are cool, cloudy and dry while August to December is sunny and dry. January to early March are hot, dry months.

The average annual rainfall is 930 mm (37 inches), varying from 1250 mm (50 inches) during wet El Niño periods to 350 mm (14 inches) during drought spells. The peak average rain months are April, May and November (see chart, below).

Temperatures vary with season and cloud cover, from 8 °C (45 °F) on chilly August morning to 28 °C (82 °F) on sunny February afternoon.

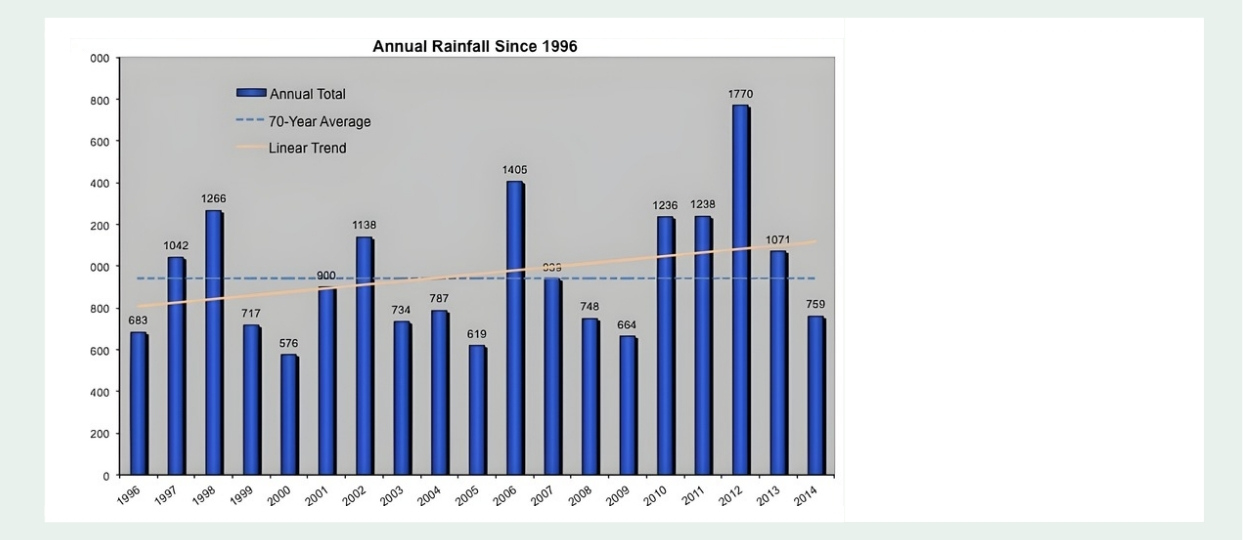

2012 appears to have been the wettest year in 67 years: nearly twice the long-term average (dotted line in the chart above). Rainfall measurements taken near Karura’s southern boundary since 1945 at the Muthaiga Country Club suggest that only the famous flood year 1963 came close to the 1,770 mm (70″) measured along the Gitathuru River.

The April 2012 total of 512 mm was the most ever recorded for that month, and December’s 300 mm was second only to Dec ’63. Moreover, records in recent years show an increasing annual trend (orange line in chart). Anyone still doubt the climate is changing?

Five perennial tributaries of the Nairobi River pass through the forest running roughly west to east and cutting through gently undulating landscape. These are:

The Karura River valley offers a precarious and stunning descent through indigenous forest to the large waterfall and the Mau-Mau caves.

Since the Late Tertiary period, during the formation of Mt. Kenya and Kilimanjaro, the region has experienced only moderate tectonic disturbances. Consequently, the parent rocks have undergone deep weathering, resulting in uniform soil profiles. In natural forest environments, this weathering produces very deep, reddish-brown clayey loam soils with slow but adequate drainage. These soils tend to become highly adhesive when wet and dry rapidly, often developing shrinkage cracks. The upper layers of soil typically exhibit a dark brown hue due to the incorporation of humus, without a significant buildup of deep litter.

In areas covered by grassland with good drainage, the soil composition closely resembles that found beneath forest stands. However, in low-lying regions subject to intermittent waterlogging, a distinct soil type emerges. These areas experience fluctuating water tables, with some fine soil material being transported downhill from adjacent higher elevations. The resultant soil in these low-lying areas is typically heavy, dark grey clay, often stained black by undecomposed humus, commonly referred to as ‘black cotton’ soil. Below the clay layer, ranging from 5 centimeters (2 inches) to one meter (approximately 3 feet) deep, a red-brown laterite layer forms. This laterite is a product of re-cementation rich in iron compounds, often associated with swampy conditions and varying water tables.

Overall, forest soils in the region are highly conducive to tree growth, except in areas with impeded drainage, such as swampy sites. These locations often give rise to natural grassy clearings, characteristic of Kenya’s upland forests.